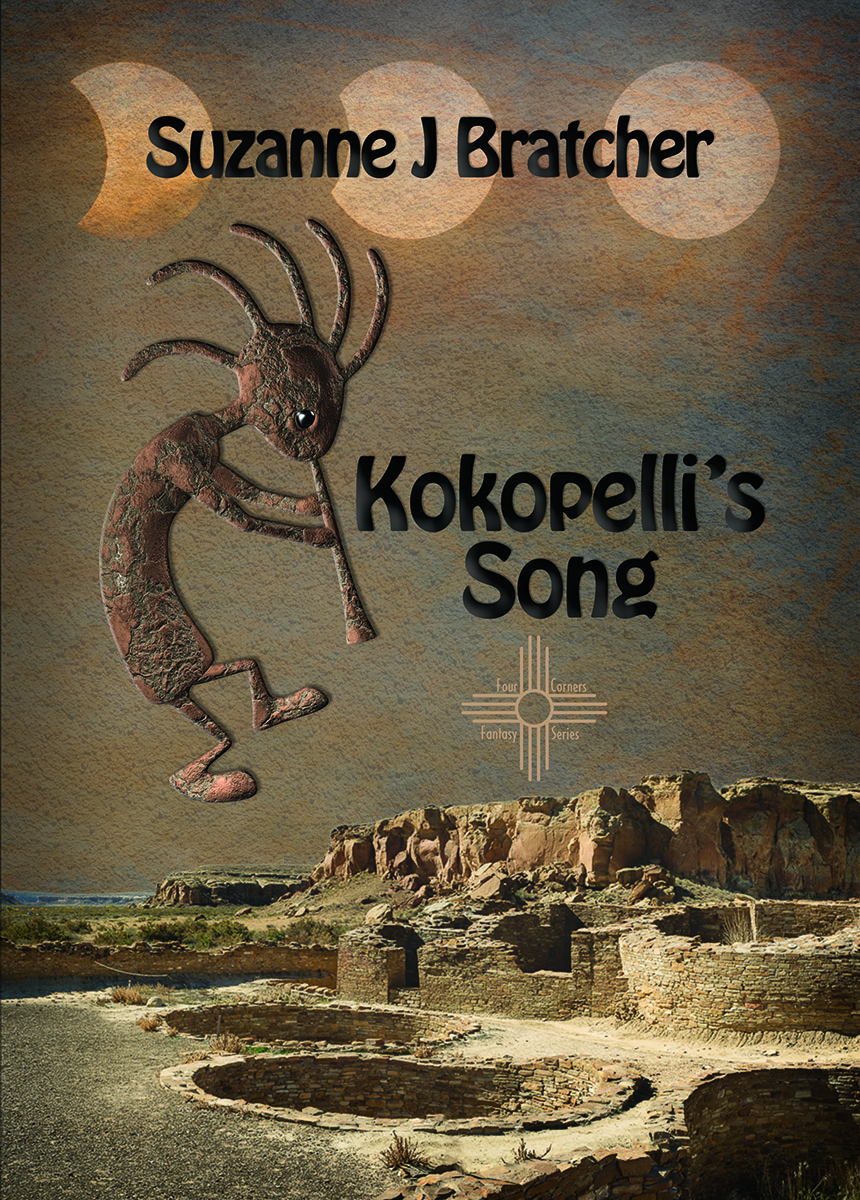

I. SIPAPUNI [Place of Emergence or Doorway]

Out on the windswept mesas of Hopiland and down in the pueblos dotted along the Rio Grande, storytellers preserve the history of the People in the times before our Time began. Each generation has its own storytellers, but the stories remain the same, passed from the old to the young.

Today, science books tell of a Big Bang, but storytellers gather the people around them and speak of music. They say the Creator sang the First World into being: the sun, moon, and stars, the oceans and land, the plants and animals, and, of course, the First People. When all was finished, the Creator taught the First People to sing. “As long as you sing the Song of Creation,” he said, “the world will be in harmony, and you will be happy.”

At first, all was well. The People sang as the sun rose in the East, while it shone directly overhead, and as it set in the West. They sang when the moon and the stars appeared in the dark canopy of Tokpela, the endless void. As they sang, they lived in harmony with creation, and they were happy. Then came a time when some of them stopped singing, then more and more. When the People fell silent, they began fighting and killing—animals and people alike. The First World fell into disharmony, and eventually the thread of life ran out.

In the midst of the Chaos, the Creator called the last of the Singers together. Heaving a great sigh, he said, “I have decided to destroy this world and try again. To keep you Singers safe, I am sending you to the Ant People.” When the Singers were deep in the earth with their brothers the ants, the Creator destroyed the First World with fire.

Then he sang the Second World into being. It was even more beautiful than the first, and the Singers were happy and multiplied. As long as they sang, the world was in harmony and all was well. But then, just as before, some of the People fell silent, and disharmony crept into their hearts. As before, more and more people forgot, and finally the thread of life ran out. Again, the Creator sent the last Singers to safety with the Ant People. And again, he destroyed the world—this time with ice.

A third time the Creator sang the world into being, and a third time the pattern was repeated. But this time when the thread of life ran out, rather than sending the last Singers to the Ant People, the Creator sealed them in hollow reeds that would float. Then he destroyed the Third World with water. For many days, the Singers drifted on Endless Water. Their food ran out, and still they had not found the place of emergence into the Fourth World. Just before they starved, they found it—the Sipapuni.

Storytellers say the world those Singers emerged into is our world. They say this Fourth World is the last chance the People have to learn to live in harmony with Creation. They say it is our last chance to keep singing.

Chapter 1

In her tiny room above the Delgado Gallery, Amy Adams punched her pillow for the third time. She flipped to her side and stared at the digital clock. Green numbers blinked three a.m. She needed sleep, but her mind trudged around the endless loop again. Grandmother Adams lied. Mahu was her twin brother. Taáta was her Hopi father. Grandmother Adams lied. Mahu was her twin brother. Taáta—

Pottery smashed on the ceramic tile downstairs. Not a small pot, one of the decorative water jars that reached her shoulder. Amy lay still, held her breath, waited for the next sound.

Mahu was down there, asleep, or maybe awake, on the long leather couch reserved for customers who wanted to consider an outrageously expensive purchase.

Amy listened for the next sound. Silence.

Heart pounding, she threw off the scratchy wool blanket and sat up. Fear like glacial runoff pumped through her veins. Not because she believed Mahu had broken a pot, but because she knew her twin was in danger. She felt it as surely as if the two of them had never been separated to grow up in different worlds.

Just like she knew Mahu was in danger, she knew whoever was with him meant evil.

Her bare feet hit the cold floor. She ran out of the room, down the dim hallway. She shivered in the sleep shirt that came to her knees, but she didn’t have time to care. In that moment, Amy was Kaya again, the older sister, the firstborn twin. The need to protect snapped at her heels, urging her to go faster, faster.

The narrow staircase cut straight down into inky darkness. Kaya Amy didn’t pause to grope for the light. Instead, she threw herself down the steps, racing to get to Mahu before someone hurt him. Before she reached the bottom, she knew she was too late.

Still she ran through the gallery, darting through a confusion of light and dark, evading ghosts of tiny bronze cowboys riding tiny bronze horses, ducking around shadows of rugs hanging from the ceiling, swerving to miss chairs carved from twisted roots and iron tables laden with painted pots.

She found Mahu on his side under the long window, backlit by the watery light of the streetlamp that illuminated the shop front. His flute and backpack lay beside him. For an instant, Amy thought she saw Kokopelli, the humpbacked flute player of the ancient petroglyphs. Then the vision was gone, and she saw her twin again.

One arm was hidden beneath his body, the other was flung back, hand clenched into a fist. A ceremonial arrow with a turquoise-inlaid shaft protruded from his chest. Not shot from a bow, stabbed in like a knife. Blood seeped from the wound, soaking his shirt. Fragments of a huge ceramic vase lay strewn around him, the one she’d heard break, the one he must have slammed into as he fell. More blood seeped from his head, spreading onto the ceramic tile floor, gathering in a pool.

“Mahu!” she cried. “Mahu!”

No answer. Only silence—silence that scared her more than a groan or even a scream. Crouching beside him, she whispered, “Mahu. Mahu.”

His long dark hair, as straight as her own, fanned out across his face. Tenderly, almost as if he slept and she didn’t want to wake him, Amy pushed back his sticky hair. The uncertain light of the streetlamp flickered across his face, one moment revealing the face of her twin, the next the face of a stranger. Not dead, she prayed. Please, please—not dead.

She wanted to find his pulse, needed to find it. At first she tried to move him, pull the closer arm out from under his body, but he was too heavy. Reaching across, she grabbed the other arm. His wrist felt warm. The fist relaxed, releasing a scrap of cloth.

As her fingers pressed and moved, pressed again, the air behind her stirred. No sound, but a warning. For the length of a heartbeat, she crouched there, clutching Mahu’s limp hand, and held her breath.

Then fingers brushed her hair.

Amy scrambled to her feet. She dodged a hand that plucked at her shoulder, lunged for the outside door. Too late, she remembered it was locked at night. But when her shoulder hit the glass, the door let her out as easily as it did customers hurrying for the next shop, dumping her into the snow-filled night with a cheery tinkle.

Cold slapped her face and sucked the air from her lungs. Ignoring the icy needles that pricked her bare arms and legs, Amy sprinted across the stone courtyard. As she passed the frozen fountain, her feet slipped. For one breathless moment she thought she would fall. But she didn’t have time.

Throwing her weight forward, she found her balance and kept running. She reached the tall wrought iron gate that should be locked. But like the door, it swung open as soon as she touched it. Behind her the gallery door tinkled again. Mahu’s attacker.

Slipping but never quite falling, she ran along the empty street past dark shops toward the hulking outline of St. Francis Cathedral. But the hope of sanctuary mocked her. Like the shops that hadn’t been broken into, it would be locked.

The gate squeaked behind her, followed by footfalls. Not bare feet like hers, feet in boots. Snow swirled around the streetlamps, transforming the moonless night into a chaos of flickering orange and yellow light. Each breath of frigid air seared her lungs, yet she ran. Faster. Around the corner. Into an alley.

Mahu’s battered pickup waited beside the dumpster. She had wondered when he tucked the keys behind the driver’s seat. ‘No one wants this bucket of bolts,’ he said with the gentle smile that transformed the unfamiliar teenager into her five-year-old twin. ‘Besides, I always believe in leaving an escape route.’

She thought he was kidding. She yanked at the door and wondered. Had he known he was in danger? Why hadn’t he warned her? She pushed the thoughts aside. No time to wonder.

Amy jerked open the driver’s door. The screech disturbed the snow’s silence. Had her pursuer heard? The cab’s overhead light shone like a beacon, signaling her location. She clambered in, reached for the keys with one hand and slammed the door with the other, extinguishing the light.

Her fingers found the ignition key, big and square. She slid it into the steering column and jammed one numb foot on the clutch and the other on the gas pedal. The engine coughed. For one frozen second she thought she’d flooded it.

It coughed a second time and then roared into life. As she pulled around the dumpster, a dark shape in a hooded sweatshirt reached for the passenger-side door. Simultaneously jerking the steering wheel and flooring the gas, she aimed the pickup at him with such force that he lost his grip and fell heavily against the dumpster.

Tires sliding on the snow, the truck lurched out of the alley into the street. Headlights could wait. She had to get away. Now. Amy swung onto Old Pecos Trail, heading for the interstate where cinder trucks would be spreading precious traction.

Unless Mahu’s attacker had parked in the same alley, she had a few minutes lead. She needed to reach the highway first. Even if he figured out where she was going, there were enough exits from the highway to throw him off track.

Amy sped around one corner, passed the cathedral, and pulled on the headlights. Ice crystals danced in the yellow light, rushed at the windshield, momentarily blinding her. She drove recklessly, hoping to find a patrolman to pull her over, return to the gallery with her, get help for Mahu.

Nothing but snow. Snow the wipers pushed at ineffectually, snow that covered her tire tracks almost as soon as the pickup made them. The streets were empty and silent, trails through an invisible city. Up a hill, sliding back, down a hill, slipping forward.

At last she saw I-25, as empty as the city streets. Amy steered madly up the entrance ramp, ignoring the clatter and clamor of the engine, willing the old pickup to keep moving. Then she entered the highway, driving on cinders already disappearing under new snow.

She pressed hard on the gas. A quick glance in the rearview mirror showed nothing but darkness. Amy exhaled the breath she’d been holding and slowed to a less frantic speed.

Heading south, she would soon leave Santa Fe behind. Amy longed for the open highway with nothing but a few exits to a string of pueblos, all off the road, shut up, sleeping out the storm. She checked the gas gauge. Half a tank. Enough to reach Albuquerque, but Mahu was lying on the gallery floor, bleeding, dying. She had to stop, had to find help.

Amy took the next exit. Cerillos Road. At the bottom of the ramp a darkened gas station occupied one corner. Across the street an all-night drugstore spilled light out into the snow. Amy parked in the deepest shadows, rested her head on the steering wheel, and tried to think.

Headlights on Cerillos Road briefly illuminated the cab, dumping her abruptly back into the present. Amy blinked. Sitting up, she pushed her tangled hair out of her face and looked down at herself. In the drugstore sign’s dim neon light, she saw her nightshirt, stiff with blood. Mahu’s blood. Panic welled up inside her. She couldn’t go to the sheriff. Couldn’t trust a man wearing a brown uniform.

Something tugged at her memory. Something scary. Something she didn’t have time to think about right now.

One thing was certain—brown uniform or not, the sheriff would say she was a runaway. He would say she belonged to Grandmother Adams until she was 18. He would call the house in Virginia, and Grandmother Adams would come for her. She couldn’t go to the sheriff, but she could call 9-1-1.

She looked at her hands, as if wishing for her cell phone hard enough would make it materialize. Her cell was in her jeans pocket, jeans that hung on the chair beside her bed.

Amy’s right hand was empty. Her left hand clutched a scrap of fabric, the piece Mahu had been holding. She knew it was important, but not now. She tucked it behind the seat where she’d found the keys and opened the glove compartment. Did Mahu have a cell phone? He had to have one. Everybody had a cell phone.

The light in the glove compartment was burned out. She rummaged in the dark, searching by touch rather than by sight. A tire gauge, a tiny spiral notebook, a broken pencil, a twisted bandana. No cell phone. With increasing urgency, she groped under the seat. No cell phone. She ran the tire gauge along the narrow space between the seat and the back window. Still no cell phone.

She found it at her feet on the filthy floor under the rubber mat. An icon indicated a missed message, but Amy didn’t care about messages. Hands shaking, she punched in 9-1-1.

“Santa Fe County Emergency.”

Doing her best to sound like a grown woman instead of a panicky teenager, Amy said, “I need to report someone badly hurt.” A voice in her mind whispered, Please don’t let Mahu be dead. Don’t let him be dead. “At 121 San Francisco Street.”

“Your name?”

“There was a break-in. Send an ambulance to the Rebecca Delgado Gallery.” She grabbed a breath, hurried on. “Send it now. Before he dies!”

Amy heard the hysteria rising in her voice. Before the woman could ask any more questions, she broke the connection and turned off the phone. She knew cell phone calls could be traced, and she didn’t want to be found. Couldn’t be found. Not yet.

All she needed was a week. Five days really. Just until their birthday, hers and Mahu’s. Once she was eighteen, she would have time to find the missing part of herself, the part of her Grandmother Adams had taught her didn’t exist, the part that lived in her dreams. She could find out who she was, where she belonged, where home was. But Mahu had to live.

Amy dropped the phone in her lap and laid her head on the steering wheel. “Please, God,” she whispered, “please let him live!”

Gradually the shock wore off, or maybe it started to set in. Amy shivered uncontrollably. Hands shaking, she turned on the engine and, without much hope, the heater. Lukewarm air stirred the winter air that leaked in around the windows, under the doors. Pulling her aching feet up under her, she tried to think. She needed help. Someone to bring her warm clothes and shoes. Someone to help her get away.

She didn’t know how long it would take the sheriff to identify Mahu or how long to find his pickup, but she did know if she wanted to keep free from Grandmother Adams, she needed to get away from anything connected to Mahu.

But who? Who would help her?

A passionate reader, I began writing as a young girl. After graduating from college, I became a teacher. Over the course of my career, I taught high schoolers, college undergraduates, and public school teachers how to write personal narratives, expository and persuasive essays, as well as poetry and short fiction. I continued to write: publishing professional articles, two textbooks, short stories, and poetry. In 2013, I won first place in Romantic Suspense in the ACFW Genesis Contest.

A passionate reader, I began writing as a young girl. After graduating from college, I became a teacher. Over the course of my career, I taught high schoolers, college undergraduates, and public school teachers how to write personal narratives, expository and persuasive essays, as well as poetry and short fiction. I continued to write: publishing professional articles, two textbooks, short stories, and poetry. In 2013, I won first place in Romantic Suspense in the ACFW Genesis Contest.

Leave a Reply